FDA Approved Drugs for Dermatology Drugs Approved in 2019

August 25, 2019

What Makes Internal Medicine Doctors Different From Other Doctors

August 25, 2019Pediatric Integrative Medicine:

Hilary McClafferty, Sunita Vohra, Michelle Bailey, Melanie Brown, Anna Esparham, Dana Gerstbacher, Brenda Golianu, Anna-Kaisa Niemi, Erica Sibinga, Joy Weydert, Ann Ming Yeh, SECTION ON INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE

Abstract:

The American Academy of Pediatrics is dedicated to optimizing the well-being of children and advancing family-centered health care. Related to this mission, the American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes the increasing use of complementary and integrative therapies for children and the subsequent need to provide reliable information and high-quality clinical resources to support pediatricians. This Clinical Report serves as an update to the original 2008 statement on complementary medicine. The range of complementary therapies is both extensive and diverse. Therefore, in-depth discussion of each therapy or product is beyond the scope of this report. Instead, our intentions are to define terms; describe epidemiology of use; outline common types of complementary therapies; review medicolegal, ethical, and research implications; review education and training for select providers of complementary therapies; provide educational resources; and suggest communication strategies for discussing complementary therapies with patients and families.

Abbreviations:

AAP —

American Academy of Pediatrics

ACIMH —

Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health

ADHD —

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

CAM —

complementary and alternative medicine

DO —

Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine

DSHEA —

Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act

FDA —

Food and Drug Administration

IBS —

irritable bowel syndrome

NCCIH —

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

NHIS —

National Health Interview Survey

NIH —

National Institutes of Health

OMT —

osteopathic manipulative treatment

RCT —

randomized controlled trial

TCM —

traditional Chinese medicine

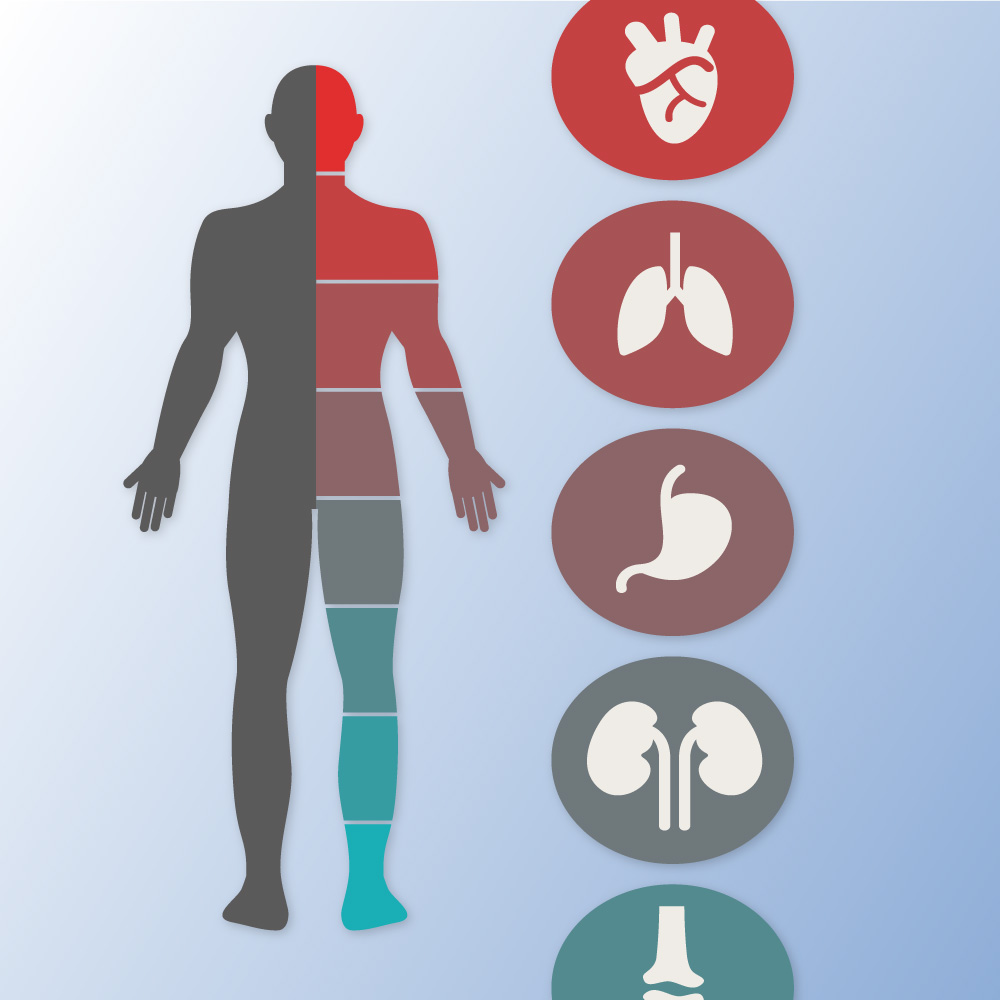

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)1 defines complementary therapies as evidence-based health care approaches developed outside of conventional Western medicine that are used in conjunction with conventional care. Examples of complementary care include the use of acupuncture to treat migraine headache2 and clinical hypnosis to improve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).3 The term integrative health describes the blending of complementary and conventional therapies by the practitioner to include all appropriate therapies in a patient-centered and evidence-informed fashion. In an integrative approach, evidence-based complementary therapies may be used as primary treatments or used in combination with conventional therapies. In contrast, alternative therapies are not evidence-based, are used in place of conventional care, and are not covered in this report.

Interest in the field of pediatric integrative medicine is driven by a number of factors, including the prevalence of use in children living with chronic illness,4,5 the desire to reduce frequency and duration of pediatric prescription medication use, and the need for more effective approaches to preventive health in children.6,7 To date, consumer interest in and use of complementary therapies has outpaced training options in pediatric integrative medicine, leaving pediatricians with a desire for more training and familiarity with resources.8 For example, a 2012 survey of academic pediatric training programs revealed that only 16 of 143 programs reported having an integrative medicine program.8 National initiatives to introduce pediatric integrative medicine into conventional pediatric residency training include programs such as the Pediatric Integrative Medicine in Residency program through the University of Arizona, initiated in 2012.9 Other teaching initiatives are underway through the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Integrative Medicine and through academic institutions affiliated with the Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health (ACIMH), a prestigious organization of more than 65 medical schools that offer integrative medicine research, education, and clinical initiatives (eg, Harvard, Yale, Duke, Stanford).10 This Clinical Report serves as an update to the original 2008 statement on complementary medicine.11

Epidemiology

Overview

Results of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) revealed that the prevalence of children <18 years using complementary therapies remained approximately 12% in the preceding 5 years,12 reflecting the fact that more than 1 in every 10 children had used some form of complementary therapy in the preceding year. In both the 2007 and 2012 NHIS, complementary approaches were used most often for back or neck pain, head or chest cold, other musculoskeletal conditions, anxiety or stress, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and were more often chosen to treat a specific condition rather than to promote general well-being.12 Nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements (eg, herbal medicines, probiotics), osteopathic or chiropractic manipulation, and yoga, tai chi, or qigong were the complementary therapies used most frequently by children in both the 2007 and 2012 NHIS.12 Zhang et al13 conducted a study in which they used data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Infant Practices Feeding Study II of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and they showed that 9% of infants, including newborn infants, received dietary botanical supplements or teas in the first year of life.

Use in Chronic Illness:

The use of complementary therapies increases to >50% in children living with chronic illness,6,12,14–18 with the most common category of complementary therapy being natural health products.12 Children with multiple chronic conditions or greater functional disability from their chronic illness were more likely to use complementary therapies.5,14,19,20 Data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement revealed that for youth with any psychiatric disorder, 5.3% received mental health services in a complementary medicine setting within the past 12 months.21

In a study of 926 children attending 10 Canadian pediatric outpatient specialty clinics (cardiology, gastroenterology, neurology, oncology, and respiratory), Adams et al4 showed that the prevalence of pediatric complementary therapy use reached up to 70%. Prevalence increased in older age groups and with severity of illness.4 The top conditions for which children used complementary therapies included various heart disorders, Crohn disease, colitis, celiac disease, epilepsy, headache, migraine, cerebral palsy, leukemia, asthma, cystic fibrosis, and other respiratory disorders. The most common complementary treatments used by this study population included vitamins and minerals, massage, and homeopathic treatments.4

Use in Adolescents

Both the 2007 and 2012 NHIS results revealed that adolescents (ages 12–17 years) were more likely to use complementary therapies than younger children (ages 4–11 years).12 In numerous reports, researchers have described the frequent use of complementary therapies by adolescents,22–26 including those living with chronic illnesses such as IBS, juvenile idiopathic arthritis,27,28 and a range of mental health conditions.21

Adolescents use supplements to lose weight, increase energy, and improve their body image or athletic performance, among other reasons. Commonly used dietary supplements in this age group include ginseng, zinc, echinacea, ginkgo, weight loss supplements, and creatine.29 The primary influences for use of complementary therapies among adolescents include their use by a family member and targeted marketing and advertising on television and the Internet.30

High Prevalence of Use, High Out-of-Pocket Costs

The 2012 NHIS showed that the prevalence of adult complementary medicine use in the preceding year remained steady at 33.2%, (approximately 1 in 3) compared with 35.5% in the 2007 survey.18 This accounts for an estimated 354 million visits to complementary medicine practitioners and an estimated 835 million individual purchases of products, classes, and materials. According to the 2012 NHIS, an estimated 59 million adults spent $30.2 billion out of pocket (with $1.9 billion spent on children) for complementary medicine practitioners and purchases of complementary medicine products, classes, and materials in the preceding year, an estimated 1.1% of total health care costs in the United States and up to 9.2% of out-of-pocket health care expenditures in 2012.31

Predictors of Complementary Medicine Use and Low Disclosure Rates

Parental use of complementary medicine remains one of the most consistent predictors of complementary medicine use in children.12 Other important predictors of complementary medicine use in children include higher parental education, higher family income, living in the western United States, and higher number of physician visits in the preceding year.6 Adults have been shown to be more likely to discuss use of complementary therapies for themselves and their children if their physician is perceived as having patient-centered communication and specifically inquires about use,32 reinforcing the key message of asking patients about all therapies in use to reduce of potential supplement-drug interactions and to promote greater trust between parent and physician.8

Patient Characteristics

The use of complementary therapies spans the socioeconomic spectrum and varies considerably among cultural and ethnic groups.19,20,33 According to the 2012 NHIS, non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic children have the lowest use of complementary therapies in the United States.12 Researchers in several studies have indicated that complementary medicine use among children may be underreported because certain ethnic populations are less likely to disclose the use of these practices to their providers.34–36 This may be in part because many cultures do not see their indigenous practices as “complementary”; rather, they are viewed as traditional approaches to health and health care indigenous to their culture. Language barriers may result in underrepresentation of non-English speakers because many of the large population-based surveys are conducted only in English.37 Reasons for the use of complementary medicine vary and include alignment with family or patient beliefs, fear of adverse drug effects, supporting conventional treatments, and desire to improve overall health.11,38 Data from the 2007 NHIS showed that patients who delayed conventional care because of financial constraints were also more likely to use complementary therapies.39

Physician Awareness, Attitude, and Perception

In the 2001 AAP Periodic Survey number 49, “Complementary and Alternative Therapies in Pediatric Practice,” most pediatricians (72.8%) agreed they should provide patients with information about all potential treatment options but reported they had little or no knowledge of complementary or alternative therapies. They recognized patients’ frequent use of these therapies and expressed a strong desire for additional education on topics, including herbs, dietary supplements, special diets, and exercise.40 More than one-third of the pediatricians reported that they or their families personally used some type of complementary therapy. Of those reporting complementary therapy use, 70% used massage therapy, 21% received chiropractic care, 13.5% consulted a spiritual or religious healer, and 13% had used acupuncture.41 In a 2005 report, the Institute of Medicine42 stated that health care professionals needed to be informed about complementary therapies and to be knowledgeable enough to discuss them with their patients. It also advocated that conventional health care professional training programs (eg, schools of medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and allied health) should incorporate sufficient information about complementary therapies into their curricula to enable licensed health care professionals to competently advise their patients about the various options.42 As of 2012, only 16 of the 143 academic pediatric programs surveyed in the United States reported having pediatric integrative medicine programs.8 As of 2015, 50% of US medical school Web sites (n = 130) listed at least 1 course or clerkship offering in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).43 These offerings embraced a wide range of topics and instructional methods. Although the extent to which pediatric residencies and postgraduate courses address educational needs about complementary therapies is unknown,44–47 there is a growing number of Web-based educational training resources in the area of pediatric integrative medicine, including the AAP Section on Integrative Medicine48 and the Pediatric Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research and Education Network.49 Since 2012, a growing number of academic pediatric integrative medicine programs have offered a complementary therapy curriculum to medical students and residents as part of their standard medical education.9 In the United States, board certification in integrative medicine is now offered to eligible candidates through the American Board of Physician Specialties.50

To ensure consistent, quality education across the spectrum of medical education, learning competencies for physician education on integrative medicine therapies should be considered for medical school, residency, and continuing medical education activities.

NIH: NCCIH

The Office of Alternative Medicine was established as part of the NIH by congressional mandate in 1992. In 1998, the Office of Alternative Medicine became the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, and in 2014 the name was changed to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. The NCCIH has increased its fiscal-year appropriations from $50 million in 1998 to an estimated $124 million in 2014 (∼0.4% of the total NIH budget).1 In the early years, NCCIH’s focus on research emphasized the importance of basic and clinical research as the core of building the evidence base for CAM.

In 2005, at the request of the NIH and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Institute of Medicine (now known as the National Academy of Medicine) released the report “Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States.” The report assessed what is known about Americans’ reliance on complementary therapies and assisted the NIH in developing research methods and setting priorities for evaluating such products and therapies. It advocated that conventional medical treatments and complementary and alternative treatments be held to the same standards for demonstrating clinical effectiveness.42

The 2016 NCCIH strategic plan identified 5 core objectives and 6 top scientific priorities and they are as follows.51

Objectives

Advance fundamental science and methods development;

improve care for hard-to-manage symptoms;

foster health promotion and disease prevention;

enhance the complementary and integrative health research workforce; and

disseminate objective evidence-based information on complementary and integrative health interventions.

Top Scientific Priorities

Nonpharmacologic management of pain;

neurobiological effects and mechanisms;

innovative approaches for establishing biological signatures of natural products;

clinical trials utilizing innovative study designs to assess complementary health;

disease prevention and health promotion across the lifespan;

clinical trials utilizing innovative study designs to assess complementary health approaches and their integration into health care; and

communications strategies and tools to enhance scientific literacy and understanding of clinical research.

The NCCIH divides the various complementary therapies into 1 of 2 main subgroups: natural products or mind and body practices. Natural products include botanicals, vitamins and minerals, and probiotics as a group (also widely known as dietary supplements). Mind and body practices include acupuncture, relaxation techniques, tai chi, qigong, healing touch, hypnotherapy, and movement therapies.